My mood was considerably changed. I suppose it was the bullets whizzing past our heads, the angry French expletives, and our narrow escape that disabused me of my fancy for finding a cozy barn to spend the night. Warm or cold, light or dark, fed or famished, we had to get to this place Ringo had directed us, buried somewhere in the Allegheny National Forest. Judging from the map it was about 30 miles further along more narrow and unlit roads.

I followed the winding country road to the intersection with PA-666, the road Ringo told us to turn on. From the moment he said it, I thought “is he kidding? Six-sixty-six?” In conservative fundamentalist homes like mine, “666” was a jinxed number, the devil’s own cipher, to be avoided like voodoo dolls and stepping on sidewalk cracks. The number should have been banned from state highway numbering systems long ago, just like the 13th floor of high-rise buildings. To the French Mafia, a jilted romantic rival, and the Ohio magistrate, Ringo was adding the Prince of Darkness and his minions to the list of adversaries we were to elude.

We shivered in the chill wind of our open-topped vehicle. The moonlight added vile premonitions to the uncanny tenor of our flight. Once in a while we passed quiet farm buildings, their windows all black. It was approaching eleven o’clock and we’d eaten next to nothing. Dimity hunkered down in the seat as much as possible to escape the cold air. The grim forests and pale gray pastures kept coming, at every turn we hoped to see some sign of life. Each new bleak and cheerless passage felt like a further descent into some cavernous abyss, each cold and lonely stretch a further advance into a heart of darkness.

At last, there, on the right was the Billy Goat Dime Store, the main feature of Kettleville. It too was lifeless and dark. But it meant that our destination was close.

“Hello and goodbye Kettleville.”

Ringo had warned us about one other thing, Linda Lou’s. On the left was an amazing house, nearly a mansion—gables, columns, wide front porch. It was probably Linda Lou’s though there was no sign.

Ringo had called it a house of ill-repute. In my naïve youth, I didn’t really know what that meant. But it had the first lighted windows we had seen in twenty miles. Ringo’s instructions were to go another ‘four point seven miles’ past it.

I noted the odometer. Each additional mile felt longer than any we had traveled so far.

At mile four and a half, I slowed down to a crawl. We looked for an unmarked dirt road per Ringo’s description. Thick hedges and trees lined the road. We could see a river in the distance on the right beyond the hedge, the map identified it as Tionesta Creek. Whatever we were looking for would be situated in the narrow reaches between the road and the creek.

Back and forth we traversed the road scanning the bushes and undergrowth, looking for any indication of an inlet. Wherever this place was, it had been completely swallowed up by undergrowth. As the hour approached midnight, both of us exhausted and stomachs cramping with hunger, I decided to head back to the only sign of life we had seen so far.

I pulled into the grassy yard to the side of the house. We dragged ourselves out of the car, up the steps of the porch, and across to the door. After one last convulsing bristle of mastery over the cold, I knocked and looked at Dimity.

“What does that mean anyway—ill-repute?” I muttered. “The house has a bad reputation? Like, oooo! Look out! The house got a bad reputation. Like it smokes cigarettes and cuts class, and—”

“It’s a whorehouse, Bo.”

That didn’t help much either. OK, a whore is…the only whore I could think of was the whore of Babylon…

The door cracked open, and one heavy-lidded eye appeared. It looked us up and down. It scanned the porch, the road, the canopy of trees overhead. It gave one long, luxurious blink, and then the door opened.

A young woman was standing before us. Young but adult, slightly taller than both of us. And I’ll just come right out and say it because a thing like this tends to bring stories and songs and traffic and everything else to a halt. The first thing I noticed, as would anyone—man, woman, child, beasts of the field or birds of the air—were her breasts. They were ample and they were out. As in out. As in loosed, present, visible, among us. I would even say, at large.

Despite her, no doubt, full comprehension of the sheer flagrance of the situation, the brazenness, despite unquestionable suspicions she would have had regarding my mental state, and the patent conspicuousness of my tender youth—despite all this, she grinned. Carelessly, blithely. Time slowed like a dream. The night was breathless. And then, unhurriedly, all too casually, as if the night chill alone had stirred the action, she pulled together her thin silk robe and tied the belt. Obviously, she was not even trying to improve this house’s reputation.

“My, my,” she said, her voice unexpectedly rumbling low.

I immediately turned around to leave and Dimity turned me back around by the shoulders.

“Hello ma’am, uh, we’ve gotten lost on the road looking for our…uncle’s house. But it’s terribly cold and…would you mind if we came in for a moment to look at our map and get warm?”

“A couple of kids out at this hour? How delightful. Please, come in.”

How could we argue? I shook my head at Dimity—oh Jiminy, I felt this was a bad mistake. What choice did we have? We stepped along behind her.

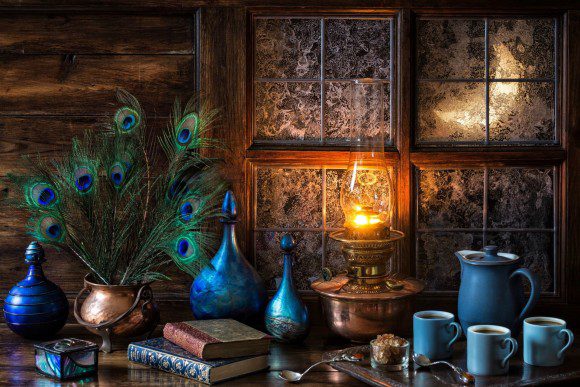

Inside we followed the woman into a bright and lavish parlor with couches and leather chairs with ottomans, tea tables with books and trinkets and memorabilia scattered around. A wide mahogany liquor cabinet and bar occupied one wall filled with numerous decanters of mysterious liquids. Lush Persian carpets covered nearly every square foot of the mosaic-tiled floors, and Flemish and Italian paintings of ships and hunting parties and intimate chiaroscuro portraits covered the walls. The ceiling was of exquisitely molded copper tiles bordered by eight-inch regal crown molding.

Inside we followed the woman into a bright and lavish parlor with couches and leather chairs with ottomans, tea tables with books and trinkets and memorabilia scattered around. A wide mahogany liquor cabinet and bar occupied one wall filled with numerous decanters of mysterious liquids. Lush Persian carpets covered nearly every square foot of the mosaic-tiled floors, and Flemish and Italian paintings of ships and hunting parties and intimate chiaroscuro portraits covered the walls. The ceiling was of exquisitely molded copper tiles bordered by eight-inch regal crown molding.

The room was copiously occupied with plant life, from blooming hydrangeas and red and purple hibiscus, to long creeping tendrils of King’s Ivy, to small trees in large ceramic pots—Ficus and lemon and fir trees. Perhaps it was the herbage that contributed so wonderfully to the crispness of the air, the absence of the type of stuffiness and the odor of leather and oil and tobacco and stale perfume you might expect in such a place. We felt our minds clearing and our strength returning.

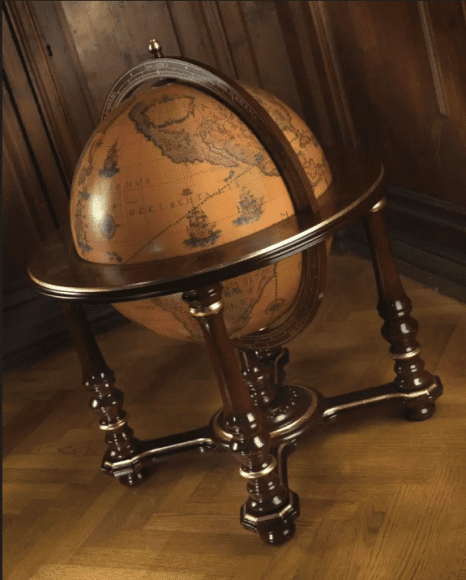

Scores of candles were lit and placed in every corner and on every flat surface. Busts of white marble were on pedestals and in alcoves in the wall, and an enormous globe was suspended in a wooden frame on rollers on the floor, ready for reference should anyone on a whim need to locate Rhodesia.

Perhaps the only odd thing about it was that there seemed to be no one else in the house.

Dimity and I felt instant relief from the cold as if we’d been released from a kind of bondage. She took my arm and breathed sighs of relief and rested her head on my shoulder. We were both exhausted. The woman indicated the nearest couch for us to sit on. She produced a tray of water crackers and anchovies and capers and deviled eggs, green and black olives, prosciutto and salami. She brought another tray with nothing but dried fruits of every nationality. Where the trays had come from, or when she’d had time to prepare them, or whether she had somehow been expecting us, I could not tell.

She brought us iceless but cool, fresh spring water in tall glasses. Then she sat down in a chair beside us. We looked at each other, smiling awkwardly, mouths full, bowing our heads in gratitude, chuckling a little at the ambrosial quality of the food. I finally swallowed my mouthful of food long enough to ask,

“So…are you Linda Lou?”

The blithe, somewhat comical smile she’d maintained ever since we’d entered the house wavered and ran away from her face. Her eyes lost their laziness and became intent now as they met ours, and she gathered the fabric of her robe together at her chest.

“Let me guess. Your uncle, is he named Reginald?”