Ringo’s Story

A shaft of moonlight from the high window mingled with the candlelight and draped the walls in shadows while lacquering our faces in amber. Ringo sat up in the bed and pulled a blanket over his bare shoulders, strangely alleviated from the ache of bullet wounds only a couple of days old. He absently scratched and pulled at the gauze bandage that circled his torso.

To say we were keenly interested would be an understatement. We were electrified. The creature revealed as Tanaquil had enchanted us from the moment we saw her. Unanswered questions about her were now about to come to light.

Somewhere outside we heard wind chimes. Ringo grew meditative and taciturn amidst a reverie of memories now twenty years behind him. His moist eyes turned to us at last.

“We are safe for a while. I’ll start at the beginning. I think I’ve told you that I left home as a young man. I was fifteen and it was in the summer of ’35. I had been working for Mr. Dalgety at the Five and Dime ever since Prohibition had ended and I needed a new way to make money. Among the dry goods, bolts of fabric, and sacks of beans, he had a small collection of books. I found and read Alexis de Tocqueville’s giant tome, as well as old copies of the National Geographic magazine.

“Tocqueville’s words broke my heart. I could see that in their pioneer ambition, the new Americans had left behind a world of intellectual wealth and beauty. The worlds of Europe and the Mediterranean, as well as Arabia and the Indus Valley, the Nordic kingdoms, the Ottoman Empire, Northern Africa—these all possessed history rich with culture, art, drama and romance, and I hungered to go there like a pioneer in reverse and make my own fortune in the old country.

“Maybe you don’t need to start so far back,” I said. “Tell us more about…” I whispered, “Tanaquil.”

“Yes, yes. I’m getting there. I left a note with my mother and father declaring my determination to return to the bosom of our cultural alma mater. I caught a bus to Baltimore, the closest and most direct maritime port. I secreted myself onboard a gigantic luxury passenger liner and was a stowaway for the three-week voyage aboard the RMS Parnassus. Within a day of setting sail, living on scraps I found in the garbage, I learned that I could earn money by covertly subverting the ship’s dining and cocktail service.

“I was considerably more fleet (and desperate) than the dining room staff. I found I could pilfer cocktail orders from the bar and deliver them along with newspapers, cigars, and any private messages to the wealthy patrons. I could perform any number of desired services. I shined shoes and recited poems. I orchestrated diversions to facilitate passage of the society of courtesans, another covert concern, who were slipping through the corridors at night. My affluent clientele preferred the discretion of a crafty youth, and some rewarded me handsomely, offering me employment or apprenticeships after we landed in Monte Carlo.

“Their generosity yielded a tidy sum in just three weeks. As a result, I was able to afford to travel around Europe and the Mediterranean. Paris, London, Aberdeen, Munich, Sarajevo, Florence, and Athens. Truly, my adventures those months could fill many books.

“Yet—and this is relevant to the story of Tanaquil—as I was being daily dazzled by all the splendor of Europe, there was the growing drumbeat of approaching war. Each passing day seemed to raise anxieties, and in every conversation in cafés and kiosks, trams and trollies there simmered rumors of distant tyranny, hatred, and anticipated invasion.”

“On the occasion when I met our mutual lady friend, I had sought escape from the persistent drizzle, gusts and cold of the winter of 1937 by going to Algiers. I had heard of the mysterious people, markets, and food of the casbah while visiting a hookah lounge in the Arab quarter of a small town on the west coast of Sicily. Magic was there, they said, secrets, and mysteries. Sources of ancient wisdom, precious substances, rare cordials, fruits, and elements found nowhere else in the world.

“Cordials had always interested me. Modern chemistry was still in its infancy, and I found a special fascination in unlocking the properties and potentialities of natural substances of the earth, and the salubrious effects of compounds of which, to quote Aristotle, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

“After I arrived and had settled with a local merchant willing to let me sleep on this floor, I was walking along the oceanfront when I chanced to see a woman in some distress sitting at a café. She looked like no other woman in that city and indeed like no woman I’d seen in any city throughout Europe. You have seen her, so you can attest to the effect I saw, her mesmerizing eyes, the elfin smile. She was enchanting, wise, and somehow aged although her face bore no wrinkles, no blemishes, no stray hairs. She wore a flowing blue caftan below jewels and a gold chain, and a black mantilla, a sign of mourning.

“Being young and now acquainted with adventure, I found it easy to make conversation and, given her obvious state and my good cheer, to say words of encouragement to her. She bade me sit down and share a pastry and some coffee. Her father had just been murdered, she said, by some foreign elements seeking to assert dominance over the country. I was shocked to hear of such barbarism, a deficiency of my youth: unfamiliarity with colonialism. To soothe and distract her, I recited my memorized poems, told her stories and riddles. I even sang some lullabies and songs to lift a heavy heart. In time, her disposition changed. At the time, I believed she was taken with me. I was winning her heart.”

“Hold on,” I said. “She told us the two of you were never romantically involved.”

“That’s right, Ringo,” Dimity chimed in. “You’d better not be telling a big fish story that contradicts her side of the story or else we’ll know! Oh, and when did she tell you her real name? Everyone has made that such a secret.”

“Yes, it seemed odd to me too. When I asked her name, she was loath to tell it to me. She withheld it that whole first day. I had happily told her my name, and she said it sounded regal. ‘Your name is that of an anointed prince. But you seem unaware of your coronation. Sir Reginald Mercette,’ she pronounced with a flourish and the gesture of bestowing a knightly accolade. But yet she became coquettish each time I asked her to reciprocate and tell me her name. She said her father warned her to guard it and not to speak it in the hustle and bustle of the common world.

“But at last, after learning that I was a young man (was she also young? Her features and manner completely concealed her age), and we shared more of ourselves, I thought I felt her heart knitting to me. At dusk, we meandered hand-in-hand out to the end of a pier where the surf surged and gurgled beneath us, and she told me.

‘Tanaquil,’ she said in an undertone. The strangest name I’d ever heard. Just to speak it somehow leaves a tingle on the tongue, like the opening syllables of an incantation.

“A deep and very special friendship arose for some days, and then friendship turned into a love affair. An impossible love affair, I came to discover. The amorous intentions and solicitations were all one-sided. Some weeks passed. When I asked her whether she loved me, she became distressed and said “Yes, of course, I do. You must know, Reginald. I love you very much.”

But when I tried to take her, to kiss her, she hesitated and demurred. Sometimes she resorted even to physically running away. She would dart off some yards away from me, to the opposite side of a brook, up on a bolder or terrace, or skirting up a tree. And she would always look down at me from the branches with a love so deep it broke my heart that I could not have her.

“But you see, as I said, she is a Sylphid. No longer an ordinary human girl as she once was. It was in her nature to love, to protect. I came to understand that it was she who was regal, and I saw that perhaps it was more the spirit of a prophetess that indwelt her. In her early life, she had indeed been both, seen mysteries and spoke prophecies, and ruled as an earthly queen. I don’t understand how such a transaction occurs, but rather than die, she was given to continue to dwell on the earth as something of a…a fairy being, I suppose.

I sprung up and started to pace the room.

“Whoa, whoa. Stop,” I said. “We are young, Ringo, but we’re not four-year-olds. Okay? Teenagers. You expect us to believe a fairy tale?”

“That depends.”

“On what.”

“On whether you believe in fairy tales.”

“Well? I don’t! Okay? Ringo? I don’t. I never have. And I thought you didn’t either. I thought we were together on that.”

“In general, Bo, I don’t. Except when I do.”

“So, she’s what…a fairy?”

“A sylphid, I believe I said.”

“Dammit, Ringo! I mean, I don’t know what to think.”

“Then listen, Bo. Listen to the rest of my story. And maybe you will see.

“We went to Italy, and I could see the conflict building in her. She had known love long before, and the memories of the joys of young love beckoned her. She resisted them. We went everywhere, all the famous places, and her mystery grew at every stop.

“As we looked at St. Peter’s Basilica, a dark solemnity brewed in her eyes. At Trevi, she smirked and chuckled at Oceanus like an old foe. In Venice, she would not swim or get in a gondola with me because she said too many souls had perished in its waters. Instead, we drank espresso and spooned sorbetto on a veranda on Lido Island as we watched the sun rise from the mists of the Adriatic.

“In Piedmont, we drank Moscato and Chardonnay from leaded crystal, and I noticed she wept and mingled tears in the glass, and when I asked what it was, she just shook her head and cut me off with a tender wave of her hand. She was lost in recollections, looking out across the valley.”

Ringo breathed a little more heavily, catching his breath as if recounting the story had taken something out of him.

“So!” he said, recovering his composure. “Thank you, my friends, for bearing with me. We come to a transition in the story. It was soon after that I learned of the dire situation in Spain, in which Nationalist usurpers under General Franco, El Caudillo, were on the march, seizing land and soon to impose his dictatorship.

“I became captivated by the story in the papers. The Fascists were gaining strength in Germany. I felt I had to go and fight their rebel counterparts in Spain. Against Tanaquil’s wishes, I enlisted as a merchant with the army of the Republic. She looked on with sadness as I flung my bulging pack and rifle over my shoulder.

Across hundreds of miles, coast to coast, and around the Spanish heartland, everywhere my platoon camped and marched and fought, she followed us hiding nearby in forests and fens and caverns, emerging only at night when she would seize me, slap my face, shake my lapels, curse my violent impulses, all the while nursing my wounds, kissing each one which left blood on her lips, sobbing in convulsions, anointing them with her tears.

“It was then I learned of her skill in mixing substances to yield amazing effects of restoration and various sorts of provocative and galvanizing impulses. Many times she was able to restore my health with a draught, and each new day my commanders were amazed at my ability to outpace my peers, to overcome the general exhaustion of war, to rise each morning and go with my full strength.

“Then in one foray, as we approached the next city on our march, unbeknownst to us, Franco’s forces were lying in wait for us just inside the city gates. We had no warning of his movements; our guard was down. It was late in the day. The sun was setting as we approached exhausted, hoping to find some food and shelter for the night when a fusillade met us. Mortar shells fell like sudden rain. Bodies collapsed in waves like dominoes. The numbers of fallen were appalling. Our infantry was scattered and I, taking a volley of shrapnel, lay on the ground among other dead and wounded, all of us exhaling our last breaths in groans.

“Bullets had pierced my lung and liver, a thigh bone—the femur, was shattered. No clever cordial could restore me this time. My wounds were too severe and I was losing blood. Breathing burned the puncture in my chest.

I managed to remain conscious as night slowly fell, gasping out words of my poems and lullabies, lying motionless amid carnage, amid the diminishing moans of so many men who had toasted me, laughed with me around campfires, their smoldering wicks now going out one by one.

“I do not remember when I lost consciousness, of course. I cheated the loss of blood by an hour beyond what I should have survived. I knew that, like the other soldiers, I was departing, and indeed, I died in the upturned grass and mud of the Spanish battlefield.

“When full darkness had fallen and survivors had been carried away, and the scavengers and bone collectors were gone for the night, Tanaquil arose from her hiding place and, like a butterfly, she came to where I lay lifeless. She tells me that she poured a mixture of calomel and Tisane tea and several other substances in my mouth and laid a coronet of acanthus leaves over my head. She hummed a song from another time and waited.

“I was unaware of any of it. But presently I awoke, able to breathe, able to walk with help. She helped me up and together we hobbled to the edges of the now-quiet city, knocking at the first apartment, falling into the first bed we could find, all dark and silent, the city seemingly abandoned.

“Together we passed the night. I slept, and she with her face and skin glowing blue, ceaselessly stroked my hair, tucking it over my ear, dabbing bits of dirt from my face. The next morning, I was alive. We determined to immediately leave the country.

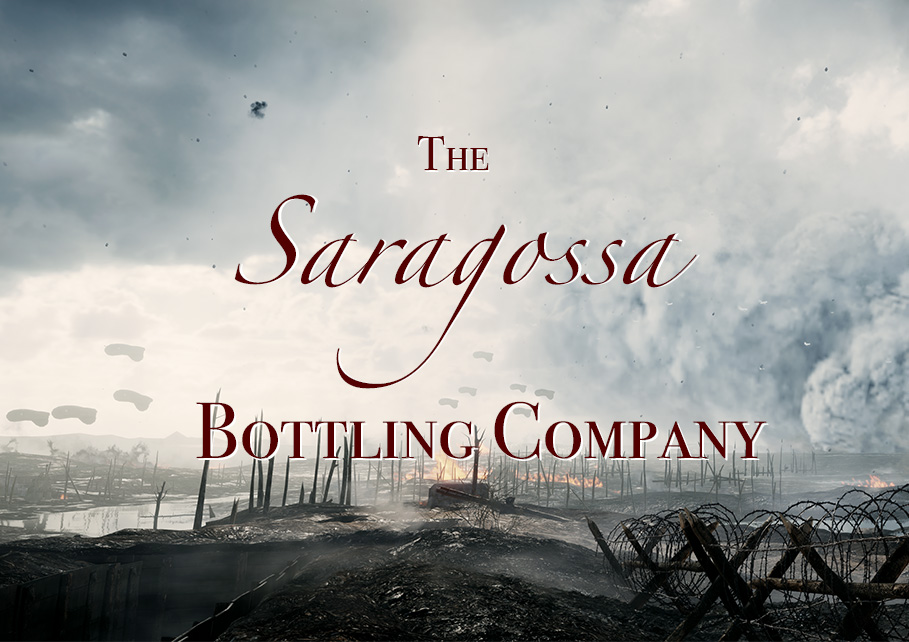

“And my friends, the city where she brought me back from death was—its name was Saragossa.”

My goodness this is fine writing. The opening sentence exquisite—even though you have a strange ability to turn sentences with the word amber in them into 24 ct literary gold. What a fine chapter! Well done.