“Listen, Ringo. When I was about eight years old, my dad took me on a snipe hunt with some of his friends. We put on our winter coats and we went out into a field late at night. My dad told me the way to catch a snipe was to sprinkle salt on its tail, so I had a salt shaker with me and a pillowcase. He also said to do the special “snipe call” he’d shown me: a high-pitched turkey-gobbling sound made while relaxing my facial muscles, shaking my head vigorously, and flapping my cheeks around.

“While he and three elders from church had coffee from a thermos and smoked cigars, I went out in the field alone. I made the snipe call. They kept saying “Louder! And try flapping your arms to make it seem like you are a snipe. That’s it, now jump up and down!” And it went on like this for an hour until I came back exhausted, miserable, having caught no snipes. They were on the ground laughing, and I realized I was the brunt of an elaborate joke.

“Do you know how that feels? Well, I vowed never to feel that way again Ringo, and I’m not starting today. I am not falling for another snipe hunt. So you can forget about your faun friend. I don’t care how much you cry; it’s all crocodile tears if you expect me to believe in elves, fauns or fairies.”

Tanaquil was now standing on the ground next to Ringo in the laboratory. The mood was a little tense and awkward. It was nice to see Tanaquil though, and I said so.

“Tanaquil, I am happy to see you again. I hope my, er, skepticism is not rude. It must be a little embarrassing for you; Ringo has this crazy notion that you are some kind of fairy. Ha ha! As for your friend who was shot, I’m sorry for him. But a faun? I don’t know. Some people just have hairy legs—”

“How old are you, Bo,” she asked in a terse voice I’d not heard before.

“Me? Well, I’m uh, fourteen.”

She looked at Ringo. “He’s too old, Reg.”

“He’s younger than I was.”

“Yes, but you were—”

“Excuse me,” I said with a polite laugh. “You see, my parents used to do this and it always drove me crazy. I mean, talking about me as if I wasn’t in the room. Can you explain what’s going on?”

But they didn’t stop it.

“What do you think?” said Ringo.

“I don’t know. He seems pretty hardened to me.”

“But he’s already seen so much. He’s tasted the elixir, he’s seen the Lurker.”

“He doesn’t want to believe.”

“He trusts me.”

“Does he?”

“I fancy he wants to be like me, at least in some ways. I hope that’s not too egotistical.”

“He wants to be scientific and…ugh! modern. He doesn’t like being a child and he can’t wait to grow up and make his way in the world. Putting him behind the wheel of a car certainly didn’t help.”

“What? No, no. On the contrary, driving a Lancia perpetuates youthfulness, my dear. It was the best thing for him. It was my plan all along.”

“Hello, Mr. Chopped Liver over here!” I shouted. “I’m standing right here!”

Tanaquil wore a pure white caftan with gold lace trim and she walked to me. Her dark brown hair hung heavily down her shoulders and framed her face like a tapestry.

“So eager to enter the adult world, aren’t you, Bo?”

“Well, sure.”

“And why is that? What’s so important about being a grown-up?”

I knew it was a trick question, but I couldn’t figure out how. Did they want me to remain a child for some reason?

“This is a strange question. Everyone wants to grow up, don’t they? I mean, you two are grown-ups.”

Ringo jumped in. “Yes Bo, but I like to think we are young at heart! That means we are open to more possibilities. Too much adult thinking can make one closed-minded and limited. You can’t teach an old dog new tricks, and all that.”

“Oh. How nice. Old people consoling their lost youth with claims of being ‘young at heart.’ Oh brother, that’s the most pathetic thing I’ve ever heard.”

“He’s too far gone, Reg.”

“Adults,” I continued somewhat bitterly, “have their fun at children’s expense. They do things like take them on Snipe Hunts and laugh at them. They make them believe in Santa Claus and the tooth fairy. They lie to kids and make them feel stupid. You’re darn right I’m ready to leave childhood behind.”

“All right, all right, all right. Listen, my friend, my blood kin,” Ringo spoke like he was placating me, but for what? I still couldn’t understand what they were getting at.

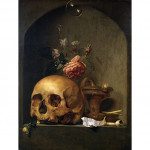

“Do you see this bottle?” He held up the little vial of green liquid. Tanaquil suddenly became animated.

“Reginald, no! You mustn’t. He mustn’t…”

“This is a kind of elixir, kind of like the concoctions you and I have been making lately. Only this one has a very particular power…”

“Give me the vial, Reginald. I never should have brought it to you. This is highly inadvisable.”

“The thing is, Bo, this elixir only works on the young. Sometimes it works even on older folks who are young at heart. If you are too adultish, too cynical, if you have completely lost a certain childish quality of innocence and wonder, it won’t work.”

“Ha!” Tanaquil gave a mocking laugh. “It could do worse than simply not work.”

“Bo, I want you to drink this. Think of joyful times in your youth. Think of your thrill when you first drove the Lancia. Think of Dimity and your love for her, so pure and innocent…”

“Not always so innocent, Ringo.”

“Oh, but she is! She’s a darling girl and you two are such a delightful couple.”

I didn’t say anything but I was remembering her languid eyes when she put four bullets in the heads of four mafiosos, and I was trembling in shock with my ear blown off. I still had the bandage on the side of my head.

“Have you ever beheld a mystery, Bo? Ever sensed that magic might be real? Ever seen something you couldn’t explain?” He was stepping closer to me holding the vial up before me.

“I, I guess so. I mean, I can’t explain everything.”

“Yes! That’s right!”

“And as for Dimity—where is she, by the way? Will she be back soon? She really likes me. I think maybe she even loves me. And hey man, I…I think…I mean, I…I do…I love her too, you know? I mean, ha! She wants to get married.”

“Yes, yes! And love is a sort of magic, isn’t it?”

“I suppose so.”

“Then, here. Drink this. It will open your eyes to the truth.”

Tanaquil was stiffened, her eyes ablaze, her mouth a taut little crease in her face. But she was not stopping Ringo. I took the bottle and shook it. Inside the sparkling green contents swirled like a snow globe.

“What is this?”

Ringo curtly shook his head. “It is the answer to your questions, Bo. Go ahead.”

I pulled out the stopper and smelled it. It had no odor at all, but the texture as it swirled in the bottle was mesmerizing. It seemed to effervesce as if it were alive, or some chemical property made it seethe and simmer in the bottle. With my eyes on both of them, Ringo tender and encouraging, Tanaquil cold and uneasy with arms folded, I tipped up the bottle and drank it.

It was salty and dirty and somehow wrong, like something that wasn’t meant to be drunk. It made my nose itch and after a minute or two, my eyes began to water. The room became unstable under my feet and I grabbed the laboratory table.

“I knew it,” said Tanaquil, throwing up her hands. “You shouldn’t have…”

“No wait! Just wait,” Ringo said.

I became short of breath and sweaty. Then I was dizzy like you feel when you are going to vomit. My vision turned to a photographic negative and I saw the two of them as dark eerie creatures with black faces and white hair. I passed out, or at least I lost myself for the next ten minutes.

When my senses returned, we were all upstairs in the living room of the house. Ringo and Tanaquil each had one of my arms and they were helping me stand upright and walk toward the door. Ringo was saying something to Tanaquil when my hearing became clear.

“We did it, my darling.”

“I hope you’re right.”

They opened the front door and we walked out into the night. I couldn’t believe what I saw.