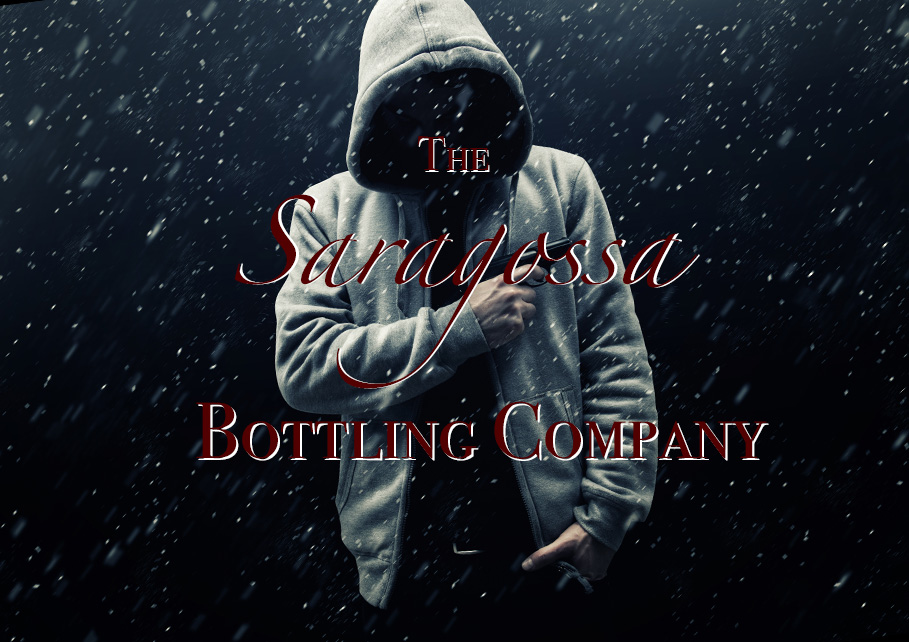

We stepped out the door into a thundering rainstorm. Ringo started the motorcycle and I got into the side car. It all seemed reckless and desperate, and frankly hopeless.

“I know some mountain shortcuts,” he said, “that she would not be able to take in a car. We can cut off at least 50 miles.”

“That’s not reassuring.”

We followed the narrow driveway out of the forest to get out to the road bumping along the muddy path in the darkness.

“I don’t see the firefly lights anymore,” I yelled. “Where are all the fairies?”

“They’ve gone inside, of course. They don’t like being out in the rain any more than you do.”

Inside what?

Ringo had a nice set of calfskin gloves, goggles, and an Army surplus fighter pilot’s skull cap. I had an ill-fitting helmet and a rubber poncho.

There was no other traffic, as one would expect during a storm on a farm road in the wee hours of the night, and this allowed Ringo to sustain alarming speeds along our winding two-lane highway.

As promised, multiple times he left the road for what looked like someone’s gravel driveway and raced down a narrow lane with tree branches lashing us on both sides. And each time we would ascend sharply, top a craggy hill, and descend even more rapidly down some hiking trail on the other side of a mountain.

My empty stomach lurched around inside my torso. I’m certain that our wheels left the ground on multiple occasions. When we were not off-roading, guided by a single headlamp over Appalachian foothills under black skies and heavy rain punctuated by lightning strikes, I tried to curl up in the sidecar and escape into my thoughts.

I had a lot of time to think about what Tanaquil had said, and what my relationship with Dimity would be after this, if any relationship was still possible, or even desired. Did she still want me? Had she ever? Did I still want her, and if I attempted to breakup with her, would I be endangering my life?

Tanaquil’s tongue-lashing was still fresh on my mind. The irony of a sylphid berating me for saying that she could not possibly exist was not lost on me. The warning that my new Second Sight could drive me to madness if not handled properly was also raw.

But I had been shanghaied and that made me angry. On one hand, I had been duped again in a kind of snipe hunt in reverse. The joke was not in being made to believe that a fake beast was real, but in being made not to believe that real beasts were fake. I was forced to believe my own unwilling eyes under penalty of insanity.

On the other hand, feeling they had my best interests at heart, adults had given me a gift beyond price. I suppose in a way it was like the shock that a baby must feel when being pushed out of the warm, dark womb into the bright, cold world. I had been born again, and like a baby, I was crying about it.

But I, at the age of 14, wasn’t just being reborn. I was being told that fourteen years’ worth molding expectations of the world was being overthrown—arguably an even more traumatic experience that being born, because an infant doesn’t have a lifetime to unlearn and re-learn.

It was a matter of accepting that the world is enchanted, that there is more to the world than what our senses and scientific instruments can detect. And why should it be so hard to believe? We all fancy that there is some magic in things; we just lack the imagination to take hold of it. It comes when we talk about “the miracle of childbirth,” or say things like, “I believe things happen for a reason.”

These were my thoughts as we spun through almost 300 miles of Pennsylvania forest and rocky mountainscapes.

Pretty insightful for an almost 15-year-old if I don’t say so myself. Where did this perspective come from? This clarity? I already knew. It was a secondary benefit of imbibing faun’s blood. I guess it’s not surprising. With Second Sight must come some capacity to live in the new world that had opened upon me.

Questions remained though. Who and what was the little boy I saw in the forest? An elf? And the faun, Chrischilde, were there other fauns? What was he doing in Tanaquil’s parlor when Lorenzo shot him?

Maybe Lorenzo reacted the way I did, the way one does when seeing a ghost: in panic, in spasms of self-defense, swinging wild punches, firing guns willy-nilly in the confusion and shock of something not understood.

But it was clear that Ringo and Tanaquil knew the faun and considered him a close friend. She is something of a queen of the forest. The Middle Folk all know her and come to her. They obey her too, the way that the Lurker had obeyed her reprimand on the first day we came into the forest.

Lorenzo was just a greasy, second-rate gangster, a loose cannon, reckless with a pistol, insinuating himself into Tanaquil’s good graces. And now he was a murderer and a true villain rather than just a racing rival and failed Casanova. Perhaps he had remorse for the unfortunate killing, but it was too late. He has hitched his fortunes to Poignard now, and that was the taking of a turn down a dark path.

Finally we began to see signs of city life. Dawn was still an hour away, but would we even notice the sunrise when it happened? The murkiness of the clouds made it seem unlikely. That was a shame because I really needed to see the sun again in light of everything that had happened in the last 24 hours.

Through the Holland Tunnel and into Lower Manhattan we coasted. We crossed the tip of the peninsula on Canal Street and then sailed over the Manhattan Bridge into Brooklyn.

My fingertips were wrinkled, my lips were chapped. With two blocks to go we stopped and escaped the motorcycle. I unfolded myself from the sidecar, and we walked the rest of the way, two soggy shadows under the streetlamps.

On the way, I showed Ringo the pistol that Mr. St John had given me back in Akron, a Browning Model 1955. He responded with an alarmed expression and motioned to put it away. I’d almost forgotten about it tucked away in my coat pocket. It was probably useless now that it was wet.

Ringo looked around to see if perchance we spotted the Lancia. We did. A block from the meeting place, there it was, conspicuous as a sore thumb.

The meeting was to be in an alley. I already knew that because I’d seen it in my dream. We hid behind a dumpster and peered down the dark lane. Someone was there. One distant streetlamp cast a silhouette of a short character leaning with one foot hiked up against a wall, just as I’d seen.

I could tell it was her by her height, her posture, her mannerisms. My heart sunk to see her like that, a denizen of the underground. Gone was my cheerleader, my spunky Australian sweetheart, at that moment betraying us to Lorenzo. It made me sick to think about it.

If Poignard got hold of the elixir and gained power to see events in the future as had happened to me, his power to control world governments might be multiplied a hundred-fold.

Did she even know what she was doing? Should we run right now and try to stop her?

It was too late. Headlights swung across and illuminated the scene. Three men in London Fogs and fedoras with bird feathers in the band emerged from the car and approached her. She also wore a fedora and overcoat, and she stood with her shoulders square, her head back and hands in her pockets, fearless, cold.

“That’s your Dimity?” Ringo whispered.

“I hardly know.”

A few words were exchanged. Dimity produced a small bottle and one of the men handed her a bulging yellow envelope. The exchange was made. She opened the envelope and seemed satisfied. A second later the men got back in the car, drove away, and Dimity was walking toward us.

She would be passing us in seconds on her way back to the Lancia. I knew we had to act fast. I nodded to Ringo and pulled out my gun. We waited for her behind the dumpster. When she passed me, I jumped her from behind, grabbed her around the neck with my arm, and put the 1955 Browning to her temple.

“Don’t move, darling.”