I learned that my favorite folk guitarist died last month in his home in Iowa.

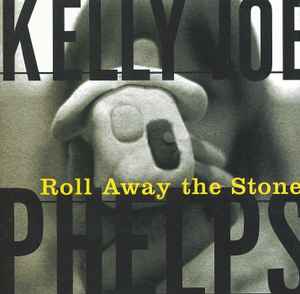

I first heard Kelly Joe Phelps play on A Prairie Home Companion back in the 90’s. It was so stunning that I scrambled to find out who that was and what was the name of his album. I bought his second CD called “Roll Away The Stone” and absolutely could not get enough of his smokey soulful voice and jaw-dropping guitar work, much of it lap-steel, all of it inspired.

I first heard Kelly Joe Phelps play on A Prairie Home Companion back in the 90’s. It was so stunning that I scrambled to find out who that was and what was the name of his album. I bought his second CD called “Roll Away The Stone” and absolutely could not get enough of his smokey soulful voice and jaw-dropping guitar work, much of it lap-steel, all of it inspired.

He completely redeemed an old hymn I sang in church growing up: When The Roll Is Called Up Yonder. The outdated, bouncy, 19th-century staple of smalltown churches everywhere received a fret-gliding, finger-picking smooth new groove. His style and originality seemed effortless, and the words which had been lost to me in the staleness of time came to life again with richness and beauty.

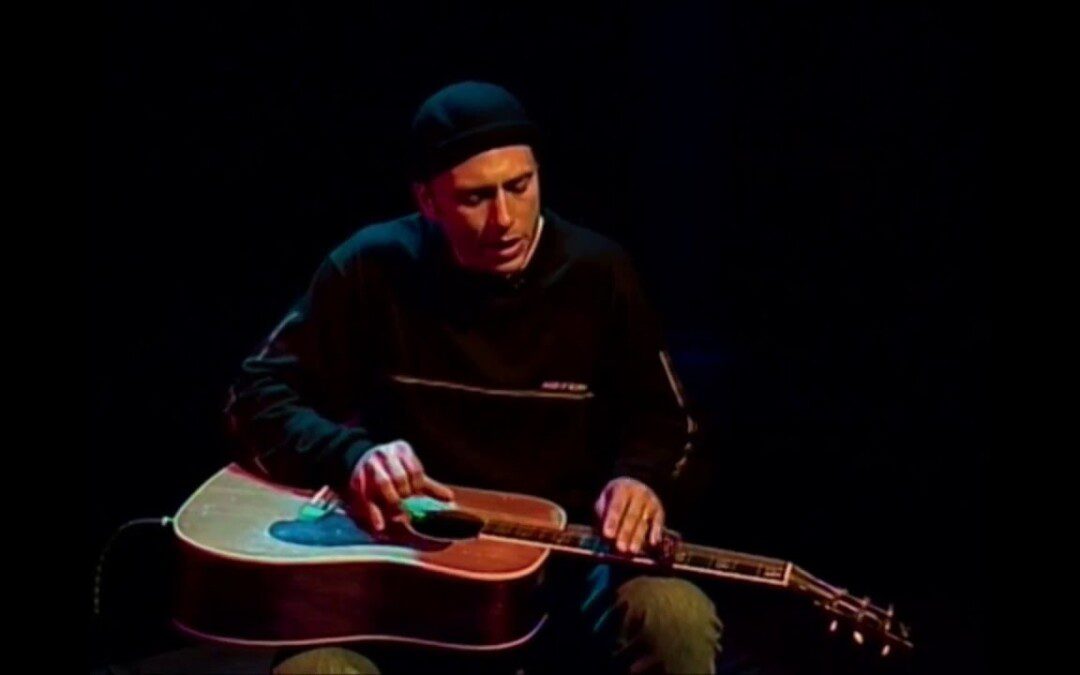

KJP changed my life. I don’t think that’s too strong of a statement. I saw an understated, humble man whose talent was otherworldly singing songs of hardship, brokenness, faith, longing, love.

On his later albums, there are many songs that I have no idea what they are about. But when he sings, “I want clean hands…and clear eyes. I wanna be a good man,” I know what he’s saying.

He exhibited faith without shame, without fear of dismissal. Such a field where performers have to clamber for attention was not his natural habitat. I could tell from recordings of his live performances that he was shy and humble.

He walked on a higher plane and seemed completely unaware of it. His music has influenced me in ways that I will never be able to put into words, more than any other folk singer. Maybe he will be blessed by that knowledge, or maybe he is not thinking about me right now.

He walked on a higher plane and seemed completely unaware of it. His music has influenced me in ways that I will never be able to put into words, more than any other folk singer. Maybe he will be blessed by that knowledge, or maybe he is not thinking about me right now.

If you haven’t already, I encourage you to find his album “Roll Away The Stone” and appreciate him posthumously. The liner notes say that the entire album was recorded in a hotel room in Washington in between passing airliners overhead.

I grieve. KJP was my favorite musician as well, a refuge I sought on innumerable occasions—and still seek often—because he sang about maintaining real faith in the midst of continuous real pain, and also because his guitar and vocal style are both entrancing and unmatched.

I did find that after repeated listening many of his obscure passages gradually come into better focus (e.g. Waiting for Marty, Jesus Make Up My Dying Bed). For others (e.g., The Circle Wars, Cardboard Box Batteries)), the meaning is all too (convictingly) obvious.